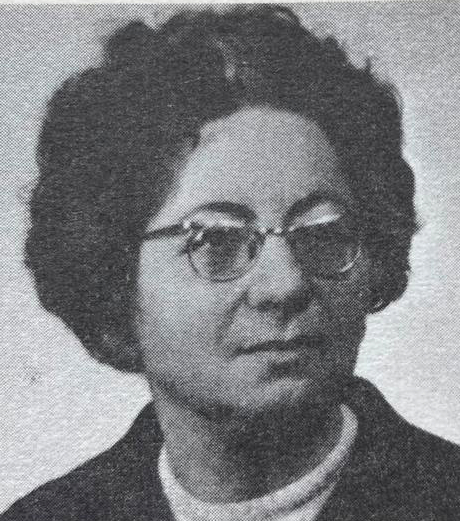

Lila Hojčová

1912 – 1989

“In addition to all the revolutionary changes that we have undergone in building a socialist society, alcoholism is a serious negative phenomenon in our lives […] Alcoholism hinders the consolidation of socialist coexistence […] it is an appeal to us to finally deal seriously and consistently with the problem of alcoholism and our interpersonal relationships. For it is unbelievable that even today we allow a husband to ‘beat his wife and children’, ‘hurt them’, ‘abuse them and threaten to kill them’.”

“Popri všetkých prevratných zmenách, ktorými sme prešli pri budovaní socialistickej spoločnosti, patrí alkoholizmus v našom živote k vážnym negatívnym javom, […]Alkoholizmus brzdí upevňovanie socialistického spolužitia […] je výzvou, aby sme sa konečne vážne a dôsledne zaoberali problémom alkoholizmu a našich medziľudských vzťahov. Veď je neuveriteľné, že aj dnes dovolíme mužovi, aby ‘bil svoju ženu a deti’, ‘ubližoval im’, ‘týral ich a vyhrážal sa, že ich zabije’.”

Blanka Királyová and Lila Hojčová, Pokrokové ženské hnutie na Slovensku 1918 – 1980, eds. with (Bratislava: Živena, 1984): 338.

Biography

Lila Hojčová, née Feuereisenová (4 May 1912, Trstená Austria-Hungary [now Slovakia] – 3 September 1989, Bratislava, Czechoslovakia [now Slovakia]) was a Slovak lawyer, sociologist, and women’s rights advocate whose legal and sociological expertise shaped institutional discourses on gender, violence, and family in state socialist Czechoslovakia.

Social background and private life

Born into a Jewish family in Trstená, Hojčová experienced intersecting forms of marginalization, due to her gender, religion, and socio-economic background. Her family owned a small business. She had two brothers, Andrej and Richard. In 1933, she married Jozef Hojč, a committed Communist, and converted to Catholicism. This conversion, however, did not shield her from the racial persecution of the fascist Slovak state. During World War II, she was forced into hiding with her young son Ivan, born in 1936. While she, her mother Viktória, and her brother Richard survived, her brother Andrej was deported and murdered in Majdanek in 1942 (her father Arpád died prior to WWII).

Educational and professional path

Hojčová credited her husband with introducing her to Marxist thought in the 1930s. Despite the significant degree to which it shaped her later political and intellectual orientation, Hojčová joined the Communist Party only in 1945. She quickly rose to leadership roles within a range of women’s organizations that operated as branches of the Communist Party or other centrally-governed institutions. From 1946 onwards, she held various functionary positions—initially at the Committee of Women under the Bratislava Regional Committee of the Communist Party, and later within the Central Committee for Women. In 1955, she played a pivotal role in the reorganization and eventual dismantling of {glossary:Živena}, the historic Slovak women’s association. Following this, she served as a leading official in the newly-formed Committee of Czechoslovak Women in Slovakia. In all of these positions she was tasked with implementing state-directed policies related to women and families.

In the late 1950s, she worked for the Czechoslovak Red Cross, where she led its Slovak Central Committee. In her later roles within the Slovak Union of Women, she directed departments focused on care for women, families, and children. She pursued her university studies later in life in the 1950s, enrolling in law at Bratislava’s Comenius University, from which she graduated in 1960 with the title Doctor of Law. Simultaneously, she worked as a party secretary at the Faculty of Arts, and in 1965 began her academic career at the Department of Sociology.

Her academic research focused on changes experienced by women under socialism, and she published articles on topics such as children’s rights, alcoholism, domestic violence, and family law. In September 1968, Hojčová was dismissed from her research and teaching position at the Department of Sociology. The official justification was that she had accepted a post as head of the socio-legal department of the Slovak Committee of the {glossary:Czechoslovak Women’s Union (Československý svaz žen)}. From 1970 until her retirement in 1977, she worked as editor-in-chief of Funkcionárka, a key women’s magazine for Slovak women in the Communist Party.

Expert work and activism

As a professional functionary in number of centralized women’s organisations; as a contributor to Slovenka—the magazine of the Central Committee of Slovak Women’s Union—and a number of other journals focusing on health and education; and as editor-in-chief of {glossary:Funkcionárka (Functionary Woman)}, Hojčová was tasked to write formal celebratory pieces for various commemorations, and reports on the visits of foreign delegations of women’s organisations. Once she graduated, Hojčová began to engage with sociological research;and her critical lens on gendered social problems started to be informed by direct experience and political commitment. She introduced deeply gendered topics, such as the conditions of women’s workplaces, or women’s and children’s health and welfare.

Most significantly, she introduced the taboo topic of alcoholism and domestic violence—issues officially seen as private or apolitical. Her 1966 article explicitly linked alcohol abuse to family violence and called for institutional intervention, using a language that resonated with the socialist ideals of family harmony and public health. She framed domestic abuse not as deviance but as systemic harm, destabilizing the narrative of the socialist family as a moral foundation. In doing so, she extended the boundaries of what could be discussed within policy and public discourse. Her 1984 co-authored book Progressive Women’s Movement in Slovakia 1918–1980 with Slovak sociologist Blanka Királyová remains a valuable historical resource.

International engagement

Though primarily embedded in domestic institutions, Hojčová also participated in international and intra-socialist exchanges. She led delegations of the Czechoslovak Union of Women to congresses in Hungary, Romania, and other Eastern Bloc countries, and took part in international expert forums such as the International Federation of Women Judges and Lawyers in Belgium. As editor-in-chief of Funkcionárka (Functionary Woman), she played a key role in facilitating East–West exchange by introducing Slovak readers to contemporary developments in women’s issues both at home and abroad, including regular coverage of the Women’s International Democratic Federation. Her multilingualism and editorial work for the Hungarian-language newspaper {glossary:Dolgozó Nő (Working Woman)} further connected Slovak women’s activism to broader transnational networks.

Research and activism with an emphasis on feminist knowledge

While dismantling autonomous women’s organizations like Živena, Hojčová simultaneously worked to build new platforms that could support gender-sensitive reform. Her political and legal work focused on improving women’s access to legal knowledge, promoting responsible fatherhood, and exposing the impact of alcoholism on family life. Her expertise contributed to what can be described as ‘networked feminist agency’—using her position within the state to articulate gendered suffering and a push for institutional responsiveness.

Legacy and impact

Hojčová shared her expertise beyond academic and popular publications, when spreading the knowledge through mass women’s movement lectures and articles in women’s magazines. Hojčová’s work remains a critical source for understanding how feminist expertise operated within—and through—state socialist structures.

Denisa Nešťáková

Selected Works

Lila Hojčová, Pokrokové ženské hnutie na Slovensku 1918 – 1980, eds. with Királyová, Blanka (Bratislava: Živena, 1984)

Lila Hojčová, Alkoholizmus a rozvoj socialistického spolunazívania, In Osveta Časopis pre otázky mimoškolskej výchovy, 1966, vol.10, no.5, pp. 51-54

Lila Hojčová, Práca komunistiek v Živene – ČSŽ, In Nové slovo týždenník pre politiku, kultúru a hospodárstvo 1950, vol. 7, no. 46, p. 275

Lila Hojčová, Ženské problémy a želania, In Naša Univerzita 1996, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 1

Bibliography

Alena Táborecká, Biografický lexikón Slovenska 3 (Martin: Slovenská národná knižnica – Národný biografický ústav, 2007)

Adam Bielesz and Vojtech Hami, “Životné osudy manželov Jozefa a Lily Hojčovcov,” Pamäť národa 2023, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 16-34

Denisa Nešťáková, “Expertise in Tension: Lila Hojčová, Domestic Violence, and the Gender Politics of Socialist Czechoslovakia,” (forthcoming, 2026).

alcoholism | Austria-Hungary | Czechoslovakia | divorce | domestic violence | law | Slovakia | sociology